Another casualty of the recent Hall of Fame selection process was Curt Flood. Flood had previously been considered by the Veterans Committee in 2003, 2005, and 2007. An outstanding hitter and fielder during the 1950s and 60s, Curt Flood sacrificed much of his career by challenging Major League Baseball’s reserve clause.[1] This time around, Flood’s name wasn’t even placed before the Golden Day Era Committee for their consideration.

The reserve clause, inserted into every white professional player contract and many semi-professional contracts including those in the Southern Minny Baseball League, tied each player to their current team for the duration of the contract and beyond as the team retained the sole right to negotiate with the player.[2] The St. Louis Cardinals elected to trade Flood to the Philadelphia Phillies after the 1969 season. The Phillies offered Flood more money to play in Philadelphia, but for Flood it was about more than money. Refusing to accept the contract, Flood said that a well-paid slave was still a slave.

Instead of accepting the Phillies’ contract offer, Flood wrote to Baseball Commissioner Kuhn demanding that he be allowed to negotiate with any major league team. Kuhn denied his request resulting in litigation that eventually reached the United States Supreme Court. Ultimately, the Supreme Court avoided the issue, finding that Congress was in the best position to regulate baseball’s interstate commerce activities. In 1975, an arbitrator effectively ended the reserve clause after two players played an entire year without contracts, allowing those players to argue there was no contract for their clubs to renew.[3]

Flood’s challenge to the reserve clause was the second such case to work its way through the courts. With major league baseball united in favor of the reserve clause, Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League offered an alternative, although a potentially costly one, for the players that accepted Pasquel’s offers. New York Giant Danny Gardella was one of the first white major leaguers to travel to Mexico after being cut by the Giants in spring training.[4]

Gardella called back to his New York teammate Sal Maglie to see if Maglie would travel south as Maglie had already been contacted by Pasquel. Maglie wasn’t interested in playing in Mexico, but Roy Zimmerman and George Hausmann were. Zimmerman and Hausman made their call to Mexico from Maglie’s room. When word of the contact with Mexico got back to the Giants’ management, all three players were cut. All three wound up in Mexico and eventually barnstormed through Austin during the Austin Packers 1948 season.[5]

Other players soon followed them south including the St. Louis Cardinals’ Max Lanier. Lanier was off to a great start for the Cardinals with six wins with no losses while holding a 1.93 ERA. Lanier wanted a larger increase from his $10,500 salary than team owner Sam Breadon was willing to give Lanier while holding the apparent leverage of the reserve clause. Breadon offered Lanier a raise of only $500 while Pasquel offered Lanier a $25,000 signing bonus and $20,000 per year for five years to play in Mexico.[6] At thirty years old, the money was just too good to pass up even as Major League Baseball Commissioner announced that any player that “jumped” to Mexico would be banned for five years.

Those bans would last until June 5, 1949, when Commissioner “Happy” Chandler withdrew them while Danny Gardella’s litigation against major league baseball worked its way through the courts. Even so, Gardella’s suit against Major League Baseball remained in play. To prevent any adverse ruling and fearing the chaos of free agency if the reserve clause was ruled illegal, Gardella was offered a $60,000 settlement.[7]

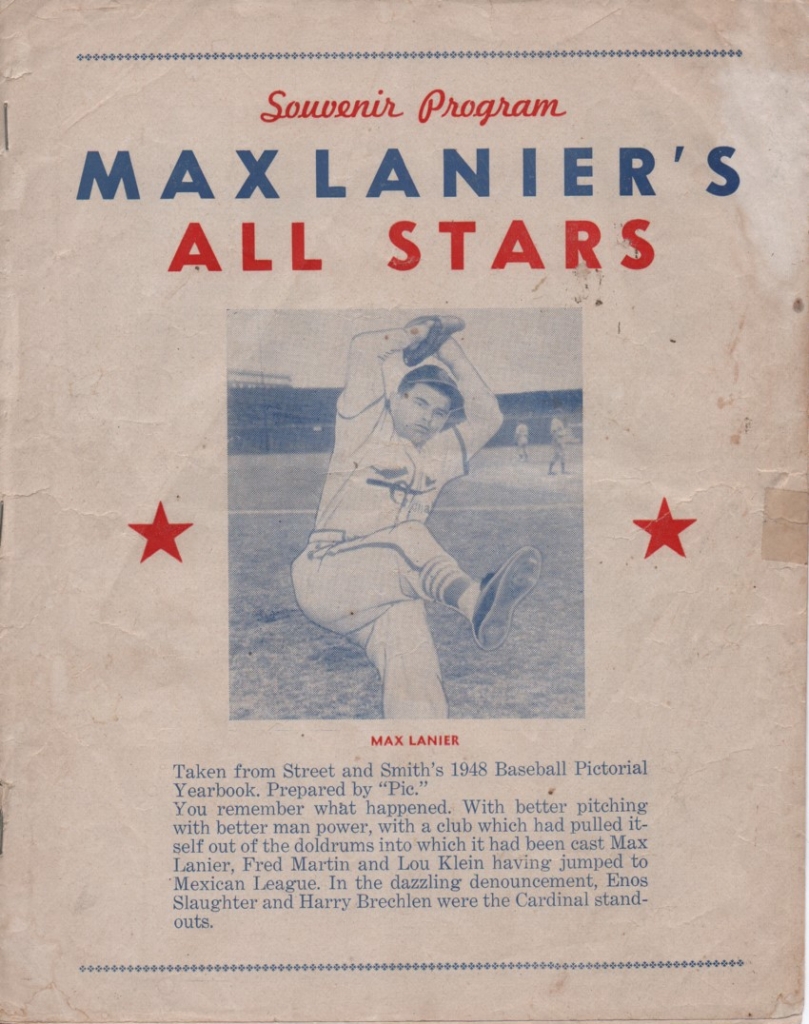

While the ban was in place, baseball players did what baseball players do: play baseball. They just couldn’t play in the major leagues or against team controlled by major league teams. Designated as baseball outlaws, many of them barnstormed across the United States as the Max Lanier All-Stars in 1948. The All-Stars visited Austin’s Marcusen Park on July 8, 1948.

The All-Stars lineup included Stan Beard at short, George Hausmann at second, Lou Klein at short and Roy Zimmerman at first base. The All-Stars starting outfield included James Steiner, Danny Gardella, and Max Lanier. Sal Maglie started for the All-Stars with Austin’s Bob Albertson tasked with holding the major leaguers in check.[8]

Albertson generally pitched well, giving up eleven safeties while walking only one. The Packers’ defense committed three errors behind him.[9]

The All-Stars took an early lead in the first on Klein’s double and Zimmerman’s run scoring single. The All-Stars added another run in the second as Myron Heyworth scored on Stan Beard’s double after reaching on a walk. Austin’s three errors in the fourth and Beard’s single resulted in two more runs in the fourth.[10]

Sal Maglie, starting pitcher for the All-Stars, would ultimately win 119 games in the major leagues. The Packers managed to tag Maglie for nine singles with Bob Beckel, Red Lindgren, and Roy Heuer collecting two hits a-piece. Beckel scored the Packer’s only run after his single, Earl Mossor’s ground out, and Heuer’s run scoring single through the box that reached centerfield.[11]

Maglie struck out ten using his curveball effectively. The All-Stars won, 5-1. Gardella, the first player to challenge baseball’s reserve clause, went 1 for 4.[12]

Maglie returned to the Giants after Chandler withdrew the ban and became one of baseball’s dominant pitchers in the early 1950’s. He started the 1954 World Series Game in which Willie Mays made “the catch” in center. He also started and pitched a complete game in a loss to Don Larson when Larson threw the only perfect game in World Series history. It was Maglie’s second complete game of the Series.

Earl Mossor and Maglie would meet again. Maglie was the starting pitcher for the New York Giants when Earl Mossor made his major league debut as a relief pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1951.

[1] Peter Dreier, “As Lockout Begins, Major League Baseball Blackballs Curt Flood – Again,” December 11, 2021, https://talkingpointsmemo.com/cafe/as-lockout-begins-baseballs-hall-of-fame-blacklists-curt-flood-again

[2] John Virtue, South of the Color Barrier: How Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League Pushed Baseball Toward Integration (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), 158.

[3] Drier, “As Lockout Begins.”

[4] Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, 127.

[5] Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, 128.

[6] Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, 141.

[7] Virtue, South of the Color Barrier, 190.

[8] “Lanier’s All-Stars Perform Tonight,” Austin Daily Herald, July 8, 1948; “Lanier’s All-Stars Down Packers,” Austin Daily Herald, July 9 1948, 7.

[9] “Lanier’s All-Stars Down Packers.”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.